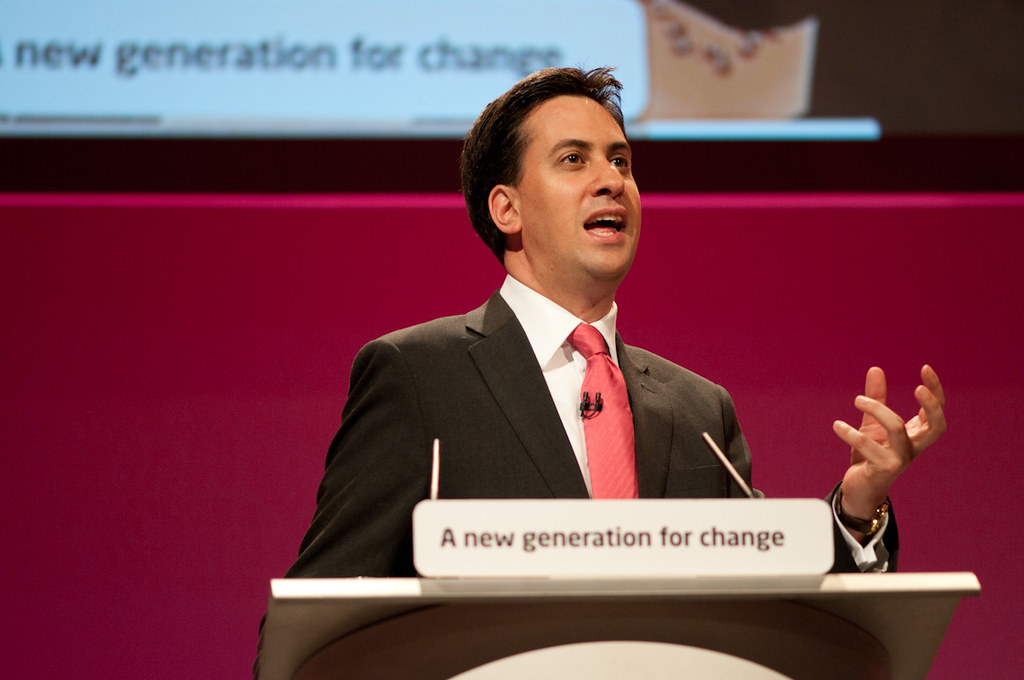

If Ed Miliband did not have a past, then he would surely have a future. If the non-Corbyn left had to come up with a politician for leader post-Corbyn, it would probably look a lot like him. Ever since his electoral defeat in 2015, the former Labour leader has proved himself to be an interesting, engaging, empathetic man: quoting Gramsci at Rory Stewart, backing Universal Basic Income with John McDonnell, or clearing simple but apparently difficult bars for some by supporting trans rights.

So why did a man that thinks and acts like this unconstrained from leadership end up posing with a monument to intolerance and a manifesto that, though wasn’t bad, strayed very far away from the sort of boldness he can now profess? Pop psychoanalysis is cheap and pointless when talking about politicians, but maybe listening to the man himself is worth it: in a recent podcast with Elizabeth Day, Miliband defines failure as “failure to be yourself”. This is probably the most accurate description of Miliband’s slog in the leadership of the Labour Party.

Unlike its cousin, Corbynism has succeeded in being a driving force for ideas while Milibandism is largely associated with eating food in a funny way. Regardless of personal feelings about the man himself, Corbyn is the means through which the ideas Miliband so clearly loves can come true. If you find yourself gritting your teeth at the worst elements of Corbynism, then you must sit down and come to terms with why it’s doing what one of the sharpest minds of the New Labour generation could not.

Part of the issue is one of legitimacy. Miliband perceived part of his authority as coming from the PLP, and could not face an open rebellion of MPs in the way that Corbyn, who perceived his authority as coming from the membership, could. This resulted in Miliband’s proposals becoming well-meaning Frankensteins that pleased nobody, while Corbyn knows that he has to please the membership (though Labour under Corbyn is subtly more authoritarian than one would expect from a man who began his career by criticizing Callaghan on the police).

In a party that will be slowly, but steadily transformed into something more member-led, this issue becomes an opportunity. Often, the so-called “soft left” (used in a loose sense, rather than the historical tradition of Neil Kinnock and the like) feels anxious about these changes, as we see ourselves trapped between the worst elements of every faction. As Bevan said, “We know what happens to people who stay in the middle of the road. They get run down”. Membership empowerment in the era of Corbyn usually leads us to believe in the terribleness of a PLP of 300 Chris Williamsons, rather than the terribleness of a PLP of 300 Chris Leslies of the Blair and Brown eras. Yet these tools must, and crucially, can be used to our advantage.

The nature of Corbynism contains multitudes: it includes the fascinating and hopeful ideas that John McDonnell proposes on ownership and the future of work, but it also houses a sort of nostalgic wide-eyed belief in “real” Labour, which has never existed and isn’t suited for the coming challenges. Its party democracy proposals have basically been a democratisation of the worst practices of the Labour right: loyalty at all costs, bullying, turning a blind eye to the frankly inexcusable. At its very worst, Corbynism is conspiracism and paranoia for a digital age, a toxic environment which will kill all its good ideas the moment they prove themselves troublesome.

If we want “real” Milibandism – the Miliband without compromises that we see now – then we must define our priorities. Work, ownership and climate change are the most important challenges we will face in the upcoming decades, and they must be tackled with ambitious ideas: a 4 day work week, a Green New Deal, a State willing to tackle the terrifying monopolies. We need to also maintain close ties to our neighbours in Europe and to the rest of the world. Nothing as existential as climate change will be solved without global collaboration, and this does mean challenging a hard Brexit, or even making the case for no Brexit at all.

These are ideas for the future that the Labour left sympathizes with, but will at times demand that they face their nostalgic elements. We cannot compromise with them on bigotry, harassment and conspiracism. We need a member-led movement that will fight these low, factional instincts, and we also need MPs willing to do so.

One of the issues with the “soft left” is that we are referred to as spineless, and if we can be brutally honest with each other, rightly so. In the coming microrevolutions, which will happen no matter who leads the Labour party, we have the tools to build a steel spine for our disappointing Milibands; we will try to build a movement that does not need to choose between Twitter accounts spilling anti-semitic threats to pregnant Jewish women or the proposals needed for a future that isn’t completely dystopic.

There is, of course, every chance the soft left will fail in this attempt. The Labour left lost for most of its existence before getting a chance. The Labour right, regardless of what it thinks, never won over the public’s mind to social democracy or the membership’s mind on every other issue. But for once, it would be good to fail on our own terms.