Now that resounding Conservative victory has been followed by leadership elections, the opposition’s focus has naturally shifted to the next general election. But this government has a free hand to tip the electoral scales, through boundary reform and voter ID legislation, while Labour must match some of history’s greatest landslides just to govern alone. Faced with the very real possibility of a further decade of Tory rule, opposition parties must not squander chances to establish alternate progressive powerbases over the next parliamentary term, win or lose in 2024. The Scottish, Welsh and London elections will take up varying degrees of attention, but the greatest scope for opposition victories will come in England’s combined authorities.

For now, the actual powers wielded by the metro-mayors are limited, though the promised White Paper on devolution could change this. But their symbolic value, as the closest thing we have to regional leadership, is immense. The eight mayoral combined authorities represent 11 million citizens. Six of them have elections scheduled within the next two years. Of these, neither Greater Manchester nor Liverpool City Region are competitive, with Labour incumbents Andy Burnham and Steve Rotherham holding vast first round leads of 39% and 41% respectively.

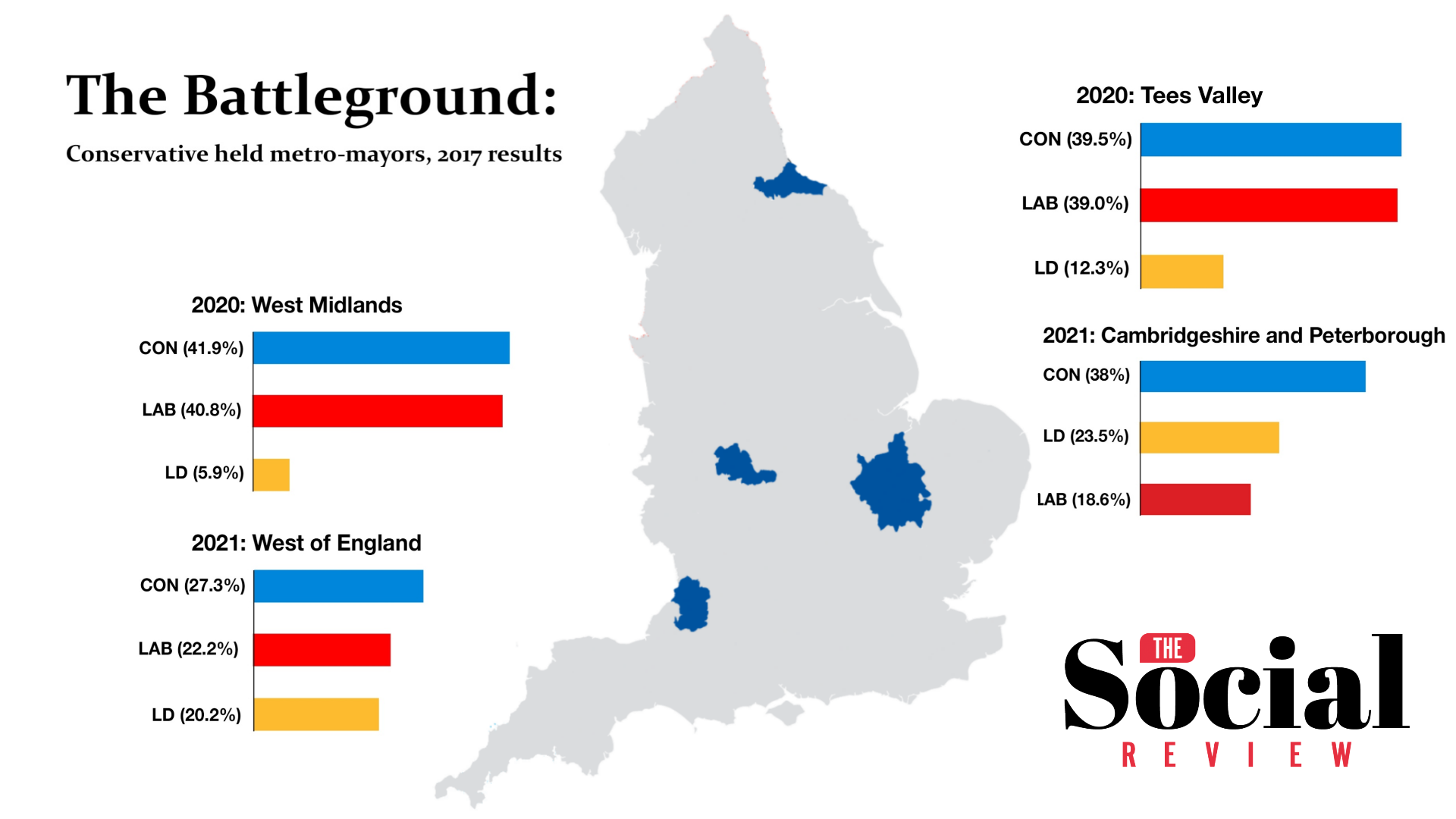

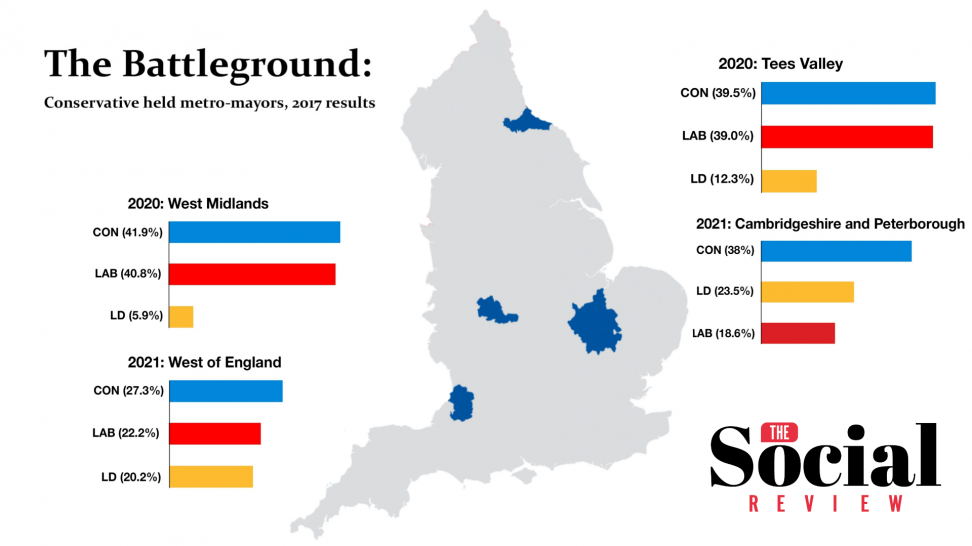

The four Conservative metro-mayors are far more vulnerable. In the West Midlands and in Tees Valley, the Conservatives prevailed by extremely slim margins over Labour in the 2017 elections. Meanwhile in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough and the West of England, narrow Conservative pluralities over a divided opposition vote were transformed into majorities by the Supplementary Vote electoral system.

While the supplementary vote takes the form of preference voting, effective use requires highly informed voters able to second guess the electorate. Each voter is given only a first and second preference vote. Should their second preference fail to make it to the second round of voting, their votes are not taken into account.

The result is highly inefficient voting, benefitting Britain’s united political right. In the extremely close 2017 West Midlands mayoral election, 60,334 Green, Lib Dem and Communist voters produced only 24,603 supplementary votes for the Labour candidate Sion Simon. Had one in ten third party voters used their second preference differently, the left would lead England’s largest combined authority, with a population just shy of that of Wales.

Last year’s enthusiasm for voting campaigns could be put to good use in the upcoming elections. However, their effectiveness will be limited in three-way races, such as in the West of England, where the second-round matchup is uncertain. In May 2017 the Labour candidate edged ahead of the Liberal Democrat in the first round, going on to lose to Conservative candidate Tim Bowles. But the 2019 elections saw the Liberal Democrats gain ground across the combined authority (see below), and it is far from clear who the most effective challenger is.

With the election taking place in 2021, serious consideration ought to be given to the race as a trial run for cross party co-operation. Opposition parties in Hungary and Turkey have used joint candidacies in mayoral elections to secure rare victories. Of course, the Conservatives are not quite Fidesz, although neither was Fidesz to start with. And a shared primary might well be beyond the realms of possibility, given the distrust between England’s two major opposition parties. But given how precarious the path back to a left of centre government has become, experiments in co-operation are highly desirable.

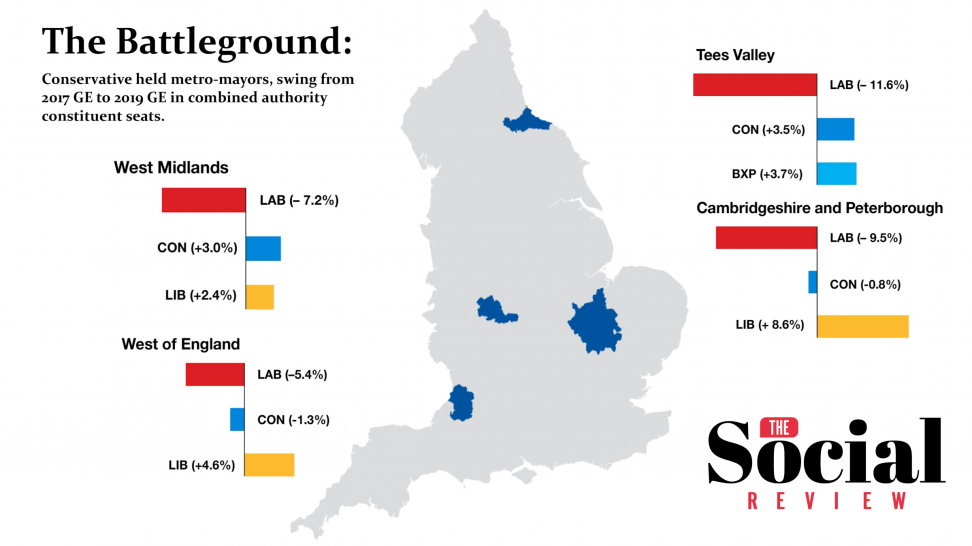

The last two years have seen substantial shifts in voting behaviour in the constituencies that make up the combined authority electorates, as seen below. These shifts should not be projected onto the mayoral results; local and national elections are not interchangeable, and the May 2017 elections took place before the bulk of Labour’s 2017 polling recovery. However, they give some sense of how the changing political geography of the UK might affect the elections of the next two years.

Labour’s decline in the West Midlands and especially in Tees Valley, combined with the bonus of incumbency, may well turn knife edge results into uphill struggles. Meanwhile the Liberal Democrats are competitive in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough, but against a resilient Conservative vote they failed to translate their surge into a single seat in 2019. The party is not short of high-profile politicians at a loose end, such as former Cambridgeshire MP Heidi Allen, who should give the 2021 race serious consideration. Opposition parties cannot take any of these races for granted and their importance cannot be lost in the heat of leadership horse-races.

Every Conservative incumbent is potentially vulnerable, if opposition parties take the upcoming elections seriously. Prior Labour leaderships have been repeatedly, perhaps unjustly, criticised for a London-centred politics. But their critics who justify reconnection with the party’s regional roots as a means of returning to power at Westminster are equally guilty. The battle for England’s cities is happening now. It ought not to be treated as an afterthought.

Notes on methodology

The boundaries of Tees Valley are not entirely contiguous with local constituency boundaries: sections of the seat of Sedgefield are outside the borough of Darlington. It has therefore been excluded from this analysis.

The Liberal Democrats contested Bristol West in 2017 but not 2019, and it has therefore been removed from swing calculations. The figure for Liberal Democrat increase in vote share across the West of England was 3.5%, but this increased to 4.5% after discarding Bristol West.

Tables available here