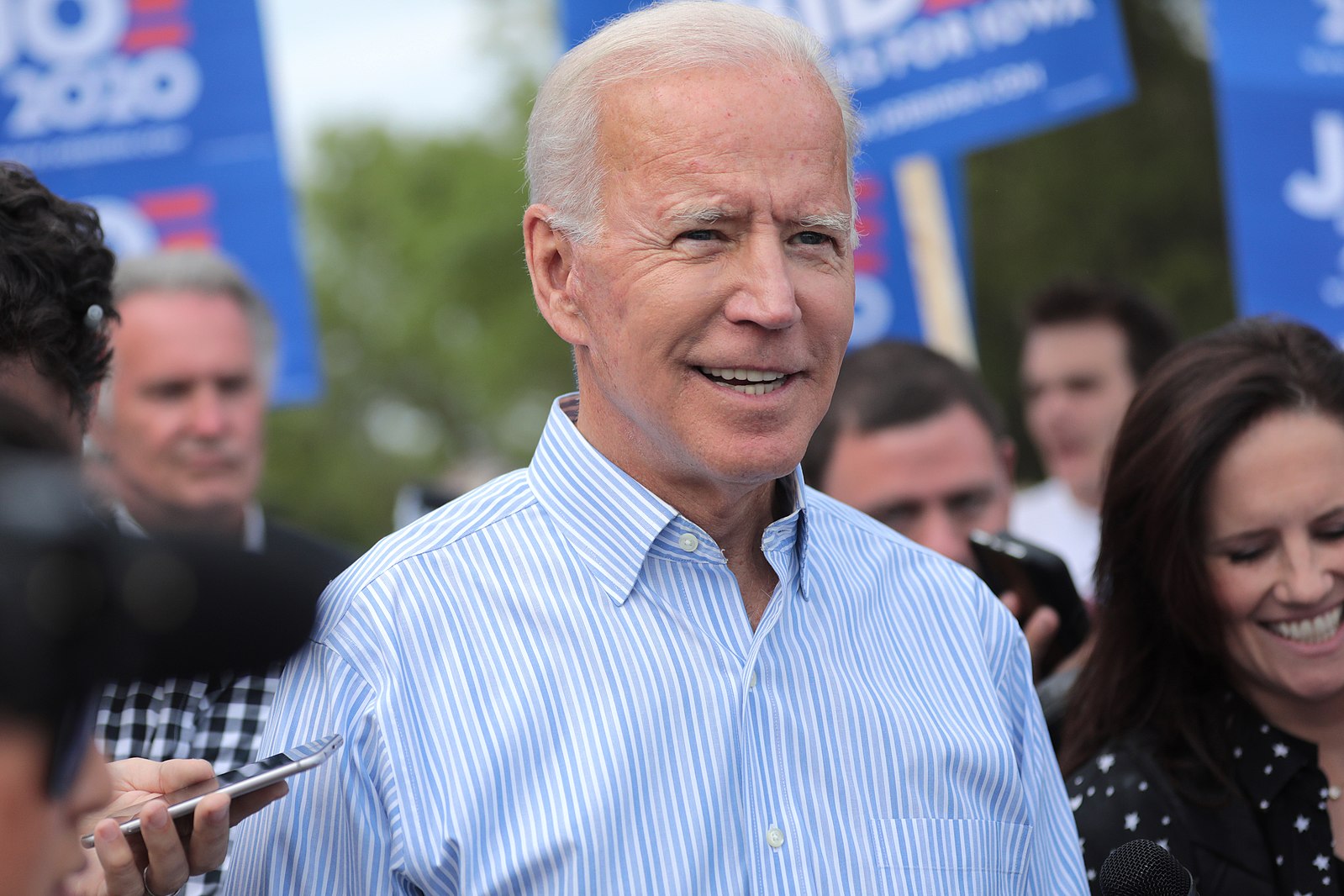

Picture Credit: Wiki

Famously, Franklin Roosevelt was described by none other than Supreme Court Chief Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes as possessing a “second class intellect but a first class temperament”. While perhaps they wouldn’t say as much out loud, one gets the feeling that this is an epithet with which supporters of Joseph R. Biden, former Vice President, 6-term Senator from Delaware and presumptive Democratic nominee, would not be too unhappy. Biden’s is not a particularly cerebral brand of politics; one of his campaign slogans is “restoring America’s soul” and his brand rests on a reputation for honest dealings and decency, on a sense of duty and patriotism forged through decades of service in a life marked by great personal tragedy. On, in short, first class temperament.

The subtitle of Branko Marcetic’s Yesterday’s Man is The Case Against Joe Biden. The case Jacobin staff writer Marcetic makes can be pretty much summarised as “second class temperament, third class intellect” (one gets the inescapable sense that Marcetic thinks his subject is, among other things, just kind of dim). The book is in largest part a blow by blow of Biden’s legislative and political career, from his election to New Castle County Council, his 1973 ascent to the US Senate at the age of just 29, his time as Vice President and on to the beginnings of his 2020 presidential bid. In this, it is faultless, well researched and more of a page-turner than it has any right to be. While Marceti gives credit where it’s due (strong on violence against women; Biden’s role in blocking the supreme court nomination of ardent Conservative Richard Bork in 1987), the book documents a half-century of bad calls, bad bills, ill-advised partnerships, and uncomfortable proximity to dealings that, if not shady, aren’t exactly in unfiltered sunlight either. From his opposition to busing to his disastrous legislation on welfare reform and criminal justice to his eulogy for Strom Thurmond to his uncritical support for George W. Bush’s war on terror (he claimed there was “no daylight” between him and the president), Biden’s is a record that leaves everything to be desired. Marcetic’s portrait is of a man almost fetishistically obsessed with the appearance of unity, of bipartisanship, without regard for its implications; a politician without any particular politics (as his former state party chairman commented, “to my knowledge, he had no particular ideology”) who is incapable of seeing the downstream implications of legislation such as his 1994 crime bill; a man whose solutions to complex problems are simplistic and whose attitude to his actions’ fallout has been little more than “aw, gee”.

As Yesterday’s Man crashes through the political world of late twentieth century America, it turns up myriad strange and unexpected details- from the involvement of key Jimmy Carter strategist Pat Caddell in doomed neoliberal beverage “new coke” (RIP) to the role of, among others, James Blunt (the “You’re Beautiful” guy, yes) in thwarting a confrontation between Russian and NATO troops in Kosovo. Among Biden’s stranger antics are a very spirited citizen’s arrest in 1980 and his bizarre plagiarism of then-Labour leader Neil Kinnock – the uncovering of which ended his 1988 bid for the presidential nomination. It’s also a great book for preposterous names, which were seemingly rife amongst Conservative lawmakers; Orrin Hatch, Richard Bork, Arlen Spectre and Byron Dorgan have all surely escaped from that 1980s Japanese video game board of all American names. Who can forget Majority Leader Sleve McDichel’s intervention in the infamous debate on the senate floor between Mike Truk, R-FL, and Todd Bonzalez, D-CA?

It’s unfair to criticise books for failing to do things they never set out to do. That being said, for all Yesterday’s Man provides ample evidence for anyone looking to support a ‘Never Biden’ argument, it is not a book which focuses much on Biden the man, and as such never really addresses Biden’s own case-for-Biden. This is a case that revolves around casting himself in opposition to Trump; as someone who does care about unity, who has experience in government, whose sense of empathy and duty grows from deep personal tragedy, first in the death of his wife and daughter in a car accident, and then the passing of his son from brain cancer. Even Marcetic admits that “Joe Biden is not a bad or evil man”; at the start of his career, Obama’s VP commented that “the one thing I want to be known for in my politics, my law practice, my personal relationships is that I am totally honest – a man of my word”. Marcetic’s case against Biden does not take aim at his honesty (though it does note that he stretched stories of his involvement in civil rights protests) or good character – it modestly limits its scope to his priorities, judgement, ambitions, record, and beliefs about how politics is and should be run. Marcetic’s is one of those books that have been scooped by events almost coinciding with its publication; his “case against Biden” is one that many had already priced in to the 2020 election, quietly filing under “we cannot have nice things” as they get ready to cast an unenthusiastic vote for the 77 year old.

Now, however, the allegations of serious sexual assault levelled against Biden by his former staffer Tara Reade bring flesh not to the case that Marcetic might bring, but to an altogether different and perhaps more convincing “case against”: the case that Biden’s nice-guy-who’s-made-some-mistakes, man of his word schtick may only be skin deep. But then again, perhaps none of it matters; given that Katha Pollit began her article on the Reade affair in The Nation with the line “I would vote for Biden if he boiled babies and ate them”, it seems reasonable to assume that much of the Democratic base is, not unfairly, just not particularly interested in Biden as anything other than a means of prosecuting the case against Trump. Come November, we will find out whether Biden’s many flaws will prove fatal in this regard.