If you’re the type that engages with contemporary left theory, chances are you’ll be familiar with “capitalist realism”; Mark Fisher’s idea that neoliberal capitalism has done such a number on our capacity for radical imagination that “it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism”. However, the affliction of the contemporary left (here covering everything from universalist social democrats to full fat communists) does not seem to be a failure of imagination: we are demanding the future more ardently than we have in some time. But from the MRP polls before the 2019 General Election (“a normal sized polling error away from a Labour majority government”) to the tantalising promise of the Sanders campaign winning Nevada, prospects of a better world seem to taunt us, turning to ash in our mouths at the brink of realisation. It’s the hope that kills you.

Into this void of political impossibility and perpetually dashed hope steps I Want To Believe: Posadism, UFO and Apocalypse Communism, A.A. Gittlitz’s new biography of J. Posadas, the Argentine Trotskyist and “patron saint of maniacal hope against rational hopelessness”. The book offers up a simple contention: in a world where all progress seems (in Gittlitz’s inference, perhaps is) impossible, what is there to lose by demanding the most costly, the most radical, the most outlandish? It’s all going to be multiplied by zero anyway. If “it’s just as realistic to fantasise about a queer commune on Mars as it is about drinkable water in Flint, Michigan”, Gittlitz asks in the book’s enjoyably deadpan style, why on earth wouldn’t you do the former? It’s just better fun, for one thing.

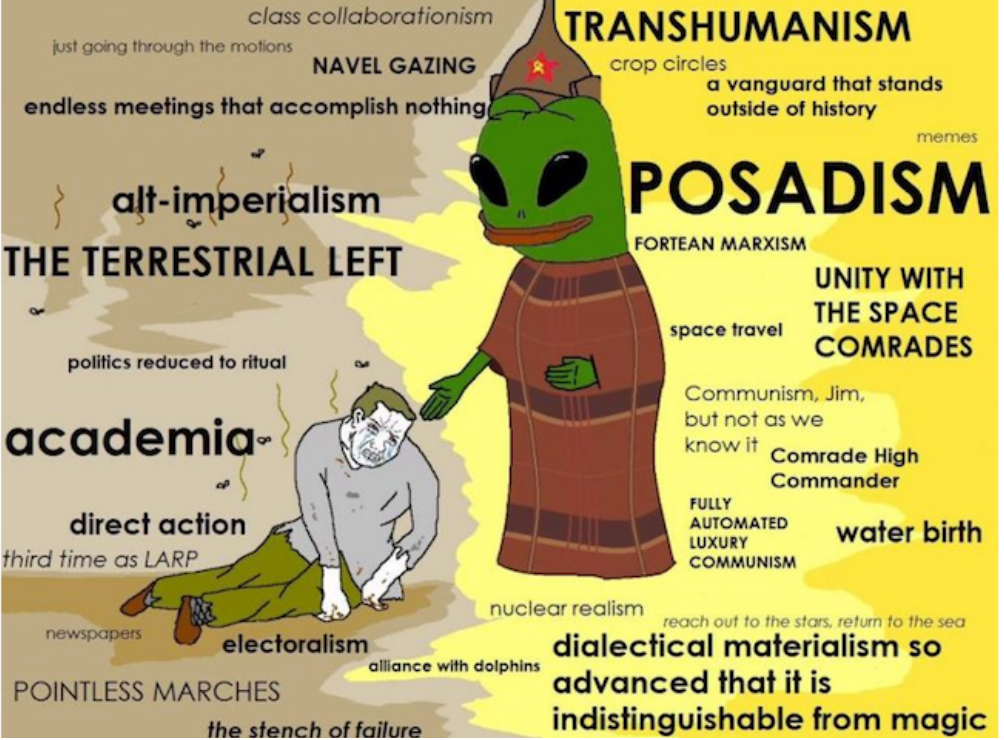

And Posadism is nothing if not good fun. By dint of its sheer weirdness and strange suitability for online culture, Posadism has climbed out of the “footnotes of footnotes” of history to achieve a certain cult notoriety. It is a variant of Trotskyism – with typical views about revolution, the workers, the means of production, Stalin (bad), all the usual stuff- set apart from the rest by three notable elements.

First among these is the belief that total nuclear war- what was termed “the final settling of accounts”- is the only way to bring about a communist utopia, and should therefore be enthusiastically welcomed by all comrades. During a particularly heated exchange on the topic at a Trotskyist meeting in the 1960s, one Posadist attendee denounced a doubting opponent “for being a pussy who doesn’t believe in thermonuclear war”, and Posadist cadres hailed what they saw as the commendably phlegmatic outlook of the Cuban people on their brush with total annihilation during the missile crisis. Being nuked back to the stone age, the Posadists felt, was a small price to pay for a classless society.

Secondly, Posadism holds that “the belief that humans were alone in the universe represents the same type of bourgeois ideology that holds capitalist class society as natural and the best of all possible worlds”. Further to this, a society that is capable of faster than light travel must, by necessity, be a communist society, because without high degree of cooperation and enlightenment such technological advances would be impossible. Ergo, there is not just life in outer space; there are comrades in outer space, and we should welcome any alien visitors accordingly. We should also, in the third tranche of popularly understood Posadism, seek to build alliances with a group of terrestrial comrades we have been heretofore neglecting: dolphins, with whom we might communicate telepathically.

I am not sure what you would expect of the man behind this mind bending mash of nihilism, extra terrestrial solidarity and peerless respect for the revolutionary capabilities of large marine mammals. Suffice to say, he did not start life as a space comrade. Born Homero Cristalli in 1912 to poor Italian immigrant parents in Buenos Aires, Posadas had a brief career as a professional soccer player before becoming a metalworker; when an industrial accident put paid to his time in this line of work (and several of his fingers), and he took up Trotskyism. The young Posadas distinguished himself with his unusual skill as a newspaper seller (Trots selling newspapers; and they say there are no historical constants), organising workers, authoring pamphlets and generally moving up in the fast-paced world of mid 20th century Latin American Trotskyism, picking up supporters along the way. In this early period he also met the woman who would become his wife, and, in a move that is either profoundly romantic or profoundly unromantic- I haven’t decided yet- proposed to her not with a ring but with a copy of Trotsky’s Transitional Programme and an invitation to join him in the struggle he saw as his life’s work. This work always came first – later, when the choice between taking his young son to hospital or studying Marxism arose, Posadas “chose Marxism”.

In this utterly po-faced commitment, we get a little of the man who would later write that humour will become passé after the revolution (because all humour is related to discomfort around property ownership, as any conscientious reader of Posadas’ “The Function of the Joke and Irony in History” will already know). Generally, however, the main flaw of the biography is that even after following Posadas’s bumpy voyage through the 20th century, it remains difficult to join the dots between the younger Posadas, an effective organiser and reasonably politically conventional Trotskyite, and the older, weirder man more recognisable as the face of everyone’s favourite extra-terrestrialist nuclear death cult.

In Gittlitz’s telling, this later version surfaces around the time of the Posadists’ 1968 clash with Uruguayan police, which led to a siege, a period of imprisonment, and ultimately exile in Italy. The biography takes us through Posadas’s involvement in various strikes and revolutionary movements in Cuba, Guatemala and across Latin America, but there is not a vast amount of insight into what prompted his increasingly devoted following and ever more monomaniacal behaviour, and with it his espousal of the bizarre creed for which he has become known. Given the well-researched nature of the book as a whole – particularly its later sections, which draw effectively on the commentary of key Posadists- it seems likely that this somewhat obscured trajectory is the result of a simple lack of sources. How and why exactly this mid range figure went from a charismatic agitator to a fully formed cult leader who referred to himself in the third person and dictated every element of adherents’ lives is unclear. Sometimes it do just be like that.

I am ambivalent about incitements to take things “seriously but not literally”, but Gittlitz’s book strikes the perfect tone in taking Posadism the right amount of both. Our contemporary appreciation for talk of the space comrades and communing with dolphins may be more ironic than sincere, but there was nothing ironic or insincere about those who committed themselves to the Posadist cause – people who fought the good revolutionary fight against the Condor dictatorships and who were imprisoned, tortured, and killed for their beliefs. It does them a disservice of a kind to treat these positions as exclusively laughable or memeable, and the biography does a good job of rationalising and contextualising views that might seem easy to dismiss out of hand. Nuclear annihilation seems a little less far-fetched when you’ve just lived through the Cuban missile crisis, and with the Drake equation fresh on the chalk board the political implications of life on other planets merited serious consideration. Gittlitz is respectful but not hagiographical, however; the book does not shy away many of the less savoury elements of Posadas, from his bizarre pronouncements on sexual abstinence (all relationships damage one’s ability to commit to the revolution; he would often demand his followers lived apart from their spouses and viewed all “non procreative” sex, even within marriage, as detrimental to the revolution) to his consistent ill treatment of his wife and devotees. This came to a head in the mid 1970s, when Posadas denounced his inner circle one by one for various perceived crimes and slights. From this point through to his death in 1981, his followers tended to be more straightforwardly in the profile of cult members: younger, and looking not for politics and revolution but for paternalism and a structure to their lives. Posadas fathered a child with a young adherent in 1975, and spent the last years of his life fixating on connecting “childbirth, pedagogy, zoology and a conception of cosmic unity”; it was in this time that his beliefs around the power of water birth to convey superhuman abilities (including telepathy with dolphins) emerged. Even if you aren’t a pussy who doesn’t believe in thermonuclear war, the positions of late Posadism were undeniably far-out.

Taken as a whole, Posadas and his ism manage to be both invigoratingly optimistic and faintly tragic. One of Posadas’ most dedicated Lieutenants, Minazolli, died in 1996, estranged from his wife and having never had children due to Posadas’ diktats, alone but for his dog, Baku – named after Mikhail Bakunin. It must be lonely, being a historical dead end; to have glued your life together with a cause only to find yourself its last all but spent spark. The death of earnest Posadism and its strange rebirth on the internet in the tumult of 2016 also begs one question Gittlitz is no more able to answer than you or I; “is it better to be cartoonishly remembered or accurately forgotten?”

The final section of I Want to Believe considers this “cartoonish remembering”. Posadism was initially re-claimed in the mid-late 1990s by Italian autonomists who, among other things, invaded the stage at a Ufology symposium and declared that “the revolution will be exoplanetary or not at all!” There were fits and starts in the 00s (the anarchist “spock block” amongst them) but Posadism had its annus mirablis in the online political sewer of 2016. I, like probably quite a few people reading this, first encountered Posadism not in the archives, but on leftbook, some time that year – my interest initially piqued, if I remember correctly, by “Posadist Paul Mason Memes”. The perverse logic and inherent nihilistic humour of Posadism slots easily into the world of the Online, but again Gittlitz choses to make a persuasive argument for Posadism as not just an offbeat blackpill, but an ideology that might have some renewed relevance in our climate change stricken world. The nuclear apocalypse may have seemed like a safe bet – but comrades, the climate apocalypse is a sure thing. Sporadic reports on the doomsday plans of the super rich- viz. surviving the climate apocalypse suggests they are as keenly aware of their class interests as ever, making ready the bunkers and the employee shock collars. Posadas felt that in the face of the “monstrous capitalist crime” of nuclear war (and what could be a better description of the climate crisis?) class unity and solidarity between workers would be so necessary as to be automatic, a universal, common sense obligation. Applying such thinking to climate change is utopian, but, in its way, almost aspirational. Gittlitz concludes on a dour note, observing that most truly novel element of Posadism from a 21stcentury perspective comes not from its doctrines on outer space but from something it shares wholeheartedly with the many less Fortean minded Trotskyist and communist groups of the 20th century (and even Tony Benn, whose diaries from his time as a Labour cabinet minister in the Callaghan administration sporadically predict the end of capitalism): wholehearted belief that the revolution was both possible and imminent.

If you find yourself afflicted by capitalist realism, a dip into I Want to Believe and the world of Posadism might be just the thing for you. Easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism? Why not both?

In the meantime I’ll be out in the garden, waving the red flag at those strange lights in the sky.