One of mine and my friend Beth’s favourite pastimes is talking about all the weird, ill conceived and forgotten novels, primarily fantasy and dystopia, that we read as children and young teenagers. We were both extremely bookish in the way that only adolescents can be, reading indiscriminately and without coming up for air, plundering book shops, school and local libraries. Born two weeks apart in the year of our lord 1995, our teenage years were something of a golden era for YA (that’s “young adult”); 13 when the first Hunger Games book came out, we are slap bang in the Twilight age bracket, just about surviving John Green’s campaign to tumblr-ify our emotional lives (okay?). Despite the glut of big name titles that were doing the rounds in our formative years, it is never these books, the ones filmed and franchised with clean-faced actresses in the leads, that we discuss in the pub. We talk about the books with plots that made no sense, or that were wildly transparent knock offs of bigger name titles. We talk about the truly bizarre and sincerely misjudged 2006 YA novel “Angel”, in which a 14 year old is groomed by some disfigured angels, and “Oh My Goth”, which is like a kind of prince and the pauper, only with goths, and which has a romantic lead named “Clarik”. We talk about bad sex scenes, endless identikit poorly written dystopias, the commendable moving weirdness of “The Knife of Never Letting Go”, the even-to-a-13-year-old cack handed Orwellianism of 2007’s “Fearless”, and about various entries in the ever popular “small animals, mostly mice and squirrels, do feudalism, inevitably ending in allegorical race war” genre.

While they make for entertaining pub chat, suffice to say that these kind of books did not make much of an impression on me. There are some books, however, that did.

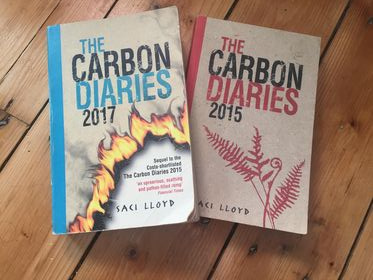

The Carbon Diaries are a pair of books by author (and 6th form teacher) Saci Lloyd, published in 2008 and 2010. Starting in 2015 (which was a long way away in 2008, when I was 12 and couldn’t imagine being 20), they follow 16-year-old Londoner Laura Brown, along with her family, neighbours and bandmates (in “screaming straight edge punk band” the dirty angels) through the first year of carbon rationing in the UK. As the nation adjusts to a radically altered set of environmental targets, the impacts of climate change, both socially and environmentally, begin to make themselves known. In the second book, Laura is at university in a much-changed London and the angels set off on tour across a Europe awash with climate migrants, water wars and neo-Nazis.

The Carbon Diaries have stayed with me far longer than any number of clunkily written supernatural romances and are, at this distance, the only books that I read (and reread, endlessly) as a teenager that still regularly surface in my thoughts as an adult. I think about them often, and recommend them often, and am reminded of them often, for the rather simple reason that they were the only books I read as a teenager that were about climate change- about its immediate realities- and they formed a large part of how I engage with a topic that I, like everyone else, now spend quite a lot of my time engaging with. With some time on my hands, I recently set about re-reading them for the first time in quite a while and set myself to thinking about just what made them so powerful.

When I was growing up, when Beth and I were reading all those naff books and you could still buy Mars Delights, it kind of felt like politics didn’t exist. Or more specifically like ideology didn’t exist; certainly, you don’t think of Bertie Ahern and Brian Cowen as primarily ideological figures (unless you count “decking” as an ideology), and the precise ideological inflections of New Labour were, uh, too subtle for my 10-year-old pallet. You get the sense that Saci Lloyd looked around the landscape of late noughties Britain and took umbrage with this dearth of ideology (or what I’m now old enough to recognise as an ideology predicated on the outward appearance of being non-ideological). Why, she asks, in an interview with the Guardian in 2010, are all the books for young people fantasy and action, about vampires and witches, when the BNP were on the rise in her own East London backyard? “If I am honest”, said Lloyd, “I sit there in front of a group of 17- or 18-year-olds, about to go out into the world, who don’t know what left-wing and right-wing means. When I was younger there was a viable political student movement, but that framework is not really there now”. You get the sense Lloyd is probably a great teacher; certainly, her books gave me more in the way of serious political education than I ever got in school, and pierced through a culture that seemed determinedly uninterested in how the world came to be the way it was. The only other book that came close was Cory Doctorow’s Little Brother (which is very good, but The Carbon Diaries are better).

With the notable exception of Britain having joined the Euro (lol), the various extreme weather events and social changes that Lloyd wrote about in 2008 could be easily plucked from 2020’s headlines, up to and including mass school strikes and out of control wildfires. There are floods and droughts and freak storms and political polarisation. The books’ accurate predictions make them distinctly depressing historical artefacts, climate wise: Lloyd is no Cassandra. All of this data was available in 2008; we have been able to see which way the wind was blowing for decades, we just didn’t look. Alongside their predictions about what our warming earth will look like, reading the books as an adult I was struck by their nuanced portrayal of Laura’s increased radicalisation, and how she grows into her own politics and asks herself what compromises she is willing to make. Over the course of two books we watch her ideas about personal responsibility, protest, violence and- very strikingly, in a world where calls to defund the police are becoming increasingly common- the police develop, as Laura and the angels fight a government by turns inert and authoritarian, a resurgent far right, and the forces of nature itself. The Carbon Diaries are also brave enough to raise questions to which there are no clear answers; in the 2nd book, Laura’s world begins to intersect with that of climate terror group the 2. Some of the characters we have followed through the series and know to be moral, thoughtful actors join the group; others reject violence. Lloyd is neither dismissive of political violence nor sentimental or coy about its impacts. This is no mean feat in a book aimed at 13 year olds.

Ultimately any novel succeeds or fails on the strengths of its characters; there’s no Twilight without Bella, no Hunger Games without Katniss, no John Green novels without thinly veiled reproductions of teenaged John Green. Coming back to the Carbon Diaries as an adult, the characters as much as the politics had stuck with me. Convincingly spirited everygirl Laura, her catty but savvy sister Kim, their quick witted elderly neighbour Arthur, righteous 6th form teacher Gwen Parry Jones, spaced out soundman Emanuel, local hairdresser turned new age match-making mogul Kieran, Laura’s punk rocking, loyal bandmates Claire and Stace- they are all so deftly drawn and vivid, you never once doubt that you’re reading about a group of real people navigating their changing world as best their can. And they are trying their best; the Carbon Diaries, for all their dark content, are remarkably uncynical books, in which good people try their best, think about their choices, try to do the right thing. Lloyd pokes a lot of fun at co-ops and women’s groups and interminable left wing meetings and lentil bakes for 60, but it’s the kind of fun you can only poke if you have sat through a lot of those meetings and eaten a lot of those lentil bakes and still, at your core, believe that these are good and worthy pursuits. At one point in the 2nd book, Laura asks Gwen Parry Jones how she keeps going, keeps caring, keeps fighting. Tiredly, her teacher replies that she just isn’t able to do other. Parry Jones is quite obviously Lloyd’s cypher, and at this moment you can’t escape the sense that the author is speaking rather directly to her audience. It’s as close as the books ever get to being preachy, and one senses that for all her jokes, Saci Lloyd is fundamentally a melliorist. She believes the world can change and be bettered and that it’s people (and punk bands) who are going to do this.

A common refrain, particularly in the post 2016 world, is that we live in the worst, darkest timeline. It’s a statement whose accuracy is impossible to ascertain, of course; human nature dictates that while we might contemplate the ways in which things might have turned out better, we are also in some corner of ourselves sure that they could have turned out a lot worse, that we and our precious timeline have snuck into at least the superior fifty percent of timelines-by-shitness. The world of the Carbon Diaries is not a happy or an easy one, and I did not expect to read the books again and find myself thinking that our timeline compares unfavourably to Lloyd’s half drowned London. But it does: in Laura Brown’s world, people are fucking livid that the planet is dying. The fictional government’s green jobs scheme- which from a real world perspective seems a borderline utopian proto-green new deal- is decried as not going far enough. In the Carbon Diaries ordinary people take to the streets and mean it, do extraordinary things to save their planet, and everyone recognises that they’re living through what just might be the end of the world, unless they do something about it. The characters are a little like the other side of the coin occupied by John Lancaster’s The Wall, where climate change has made people hateful and shrivelled. But not in the Carbon Diaries; they are books where people rise to the occasion, and make the young reader feel that this is something that they could do, too.

I don’t read children’s books anymore, because I am 25 and busy feuding with my landlord and trying to understand Chantal Mouffe. I have no idea what 14 year olds read, but I have faith in their literary tastes lining up with their generally good politics on the climate crisis. I think it’s probably the case that the Carbon Diaries would not be so singular if published today, but way back in the bad ol’ post Potter, Darren Shan self insert fanfic, John Green Youtube channel days, they were all I had. And for that, I will always be grateful.