I went to the vigil on Clapham Common last night with two of my best friends. On our way there we talked about a friend of ours who had reported an abusive partner to the police, and was met with something close to polite disinterest. We talked about someone else we knew who had taken her abuser through the courts, all the way to that rarest conviction, only to see him get off with community service and a fine. He still works in a school- the headteacher wrote him a glowing character reference read out in court after 12 jurors concluded that this man was guilty of the abuse for which he was charged. We talked about the time a man followed me home at 3am, all the way from Bethnal Green tube station to the top of Brick Lane, and when I finally broke and ran he followed me up onto the walkway of our block of flats, when by some miracle, a late night trip to put the bins out that was truly blessed by a higher power, a neighbour emerged and blocked his way and I escaped. I am not interested in sharing these stories for the purpose of educating men on social media. I am not interested in sharing twee advice on how men can make us feel safer. I am interested in talking about the world I live in, as I live in it, with women, with my sisters, with my best friends.

Some years ago my friends and I went mad together, truly off the misandrist deep end into a fevered perpetual rage at a world that we felt offered us, at best, little more than sexualised contempt. These days we often joke about this period, at how we would bark and howl at men in the street who looked at us funny, but as we headed down to south London in the early evening we did not joke as we talked about that time. Michelle Tea, in her essay on the SCUM Manifesto, has written about the time in her life when she wanted to blow up a frat house: “I was very serious. I thought it would be fairly easy and we could probably get away with it, and if we didn’t I was actually prepared to go to prison for my part in this war. Because that’s what it was, a war. Men got to do anything to women and women got to walk around scared and traumatized and angry. Men got to do anything, period. Men got to do everything. Something had to take them down”. At one point in our lives, this is how we felt, the three of us. We would have blown up a frat house, probably. I’m more respectable now and I’m used to smiling with my teeth when my male friends ask me if I really meant all this, but this week, as I watched the news, as we were told to disperse by the police while participating in a vigil of 15 people outside New Scotland Yard, I have felt something like this again. That hunted, ragged feeling of being aware at all points of the day that you are moving through a world that is unsafe; like the floor is moving and you have learned to step with it, almost without thinking, but when you realise what you are doing, this dance you do everyday, you feel insane, feel like you could do insane things.

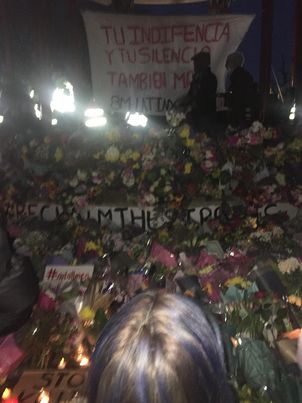

When we arrived at Clapham Common, a crowd had already gathered, peacefully ringing the bandstand, doing what we had all gathered to do, to mourn, to feel our sorrow and our anger and our sisterhood together. It was getting dark. People had laid flowers. Without prompt, we saw police begin to move through the crowd, up onto the bandstand, clearing people in scenes that will now be familiar to anyone who has been on social media in the last 24 hours. The crowd shouted and chanted and moved as the police began to drag away people who like us had come to mourn, to feel their anger and their grief. The Met have since released a statement saying they had no choice but to step in because of the “overriding need to protect people’s safety”. I am not going to credit this. No serious person believes this. I do not need to tell you the obvious; that the presence of the police at a vigil remembering a woman for whose murder a police officer has been charged was unwelcome to begin with; that their violent disruption of the event shows they know exactly whose side they are on. At the bandstand the night air smelled of flowers, from all the bouquets laid out underfoot.

We continued to watch the police, who shoved at us, told us to go home. We didn’t, and eventually they left, and we were allowed to do what we had come to the Common for. We stood in silence together and thought about Sarah Everard and the man who has been charged with her murder. This is a man whose job was to protect people; specifically, actually, his job was to protect my own workplace. I have probably interacted with him. My friends have probably interacted with him. Culturally, we like the idea of the lurking pervert, the entirely societally beyond the pale man who stalks the streets late at night, as if this is his full time job, his role and his role alone. The reality is that the dangers are in our structures; in our schools and homes, in our workplaces. They are the police. They are a feature, not a bug, and all we have in our defence is sisterhood.