I’m a Liverpool fan, and have been since I was about six. Ask me for the greatest moments as a supporter and I will be reeling off to you the great comeback stories in European nights at Anfield, beating Manchester United, Steven Gerrard’s thunderbolts. I’m not telling you about how great it was to win the League Cup in 2012. Even the 2019 Champions League win is remembered less for the glory than it is for how we turned over Barcelona. That is what football is about: raucous, lung-burning noise, the warmth of the collective, the feeling of solidarity and belonging.

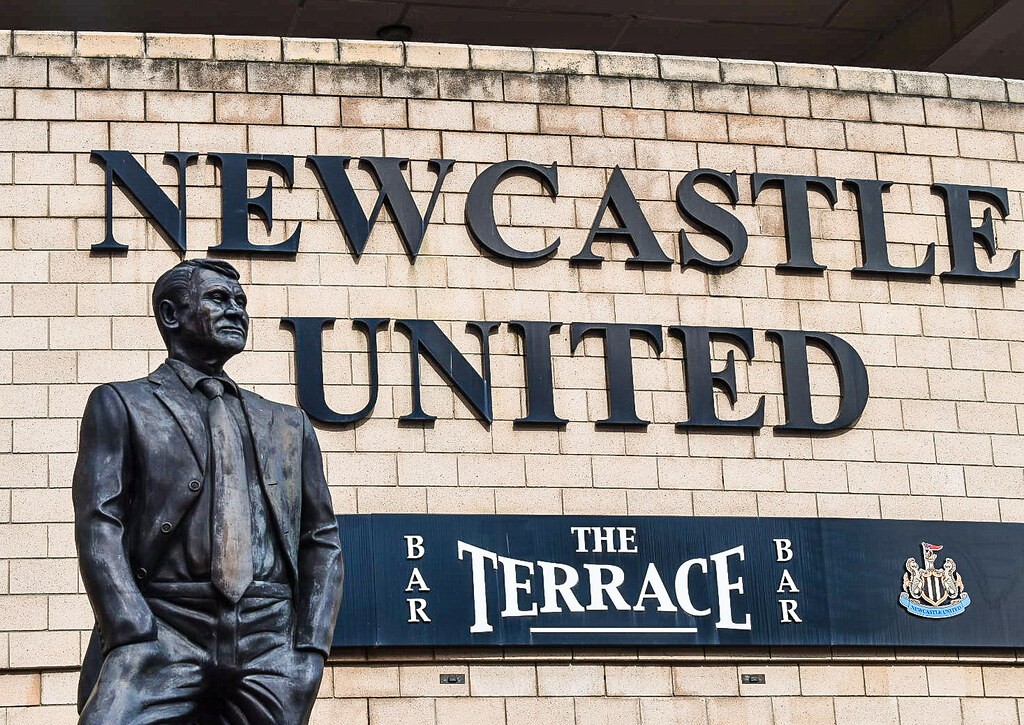

Yet this is not what makes the world of football go around; increasingly, fans are having to face the facts that their clubs are multi-billion business, and they will be treated with the sort of moral truculence that marks all transactions of the sort. The most recent example comes in the form of Newcastle United’s acquisition by a Saudi-led consortium.

The takeover was a long time coming. A £300m bid by the Saudi Public Investment Fund(PIF) was completed after the Premier League accepted “legally binding assurances” that the Saudi state would not control the club. This would be a laughable notion for any sovereign wealth fund, but for one which is chaired by the Saudi Crown Prince it is farcical. The size of the PIF’s wealth dwarfs even that of Manchester City’s and completely reshapes the game in terms of who can afford what.

One could be forgiven for thinking that the Super League lost the battle and won the war. The failed project that would have turned football clubs into franchises and created a closed shop was derided for killing competitive spirit; however, looking at English football now, it’s easy to envision a future where the Premier League will resemble a variation of the Super League.

Having languished in obscurity for years, dreaming of their better days in the nineties, Newcastle United have been woken up by the reality of ruthlessly cruel despotic theocracy willing to buy their way back to the top. Saudi Arabia’s infiltration in the game was all but unavoidable; this was a precedent established by allowing Abu Dhabi and Qatar to purchase Manchester City and Paris Saint Germain respectively. The game has long since opened the door to such dictatorships. The scale of the purchase, as well as its symbolic significance, however, begs the question: How can the proudly competitive English football tradition survive this?

The globalisation of the game brought the vultures circling around clubs that would be ripe for their PR projects. Football clubs are local community assets but they have been run – and failed – as global capitalist enterprises. In a world where young boys from countries such as Brazil, Argentina or Chile dream of playing not at home, in their own local teams, but to the highest paying club in Europe, the game is cut across with a feeling of corporate exercise. It’s no wonder that supporters at home are regularly squeezed for high ticket prices or have a high level of unhappiness with how their clubs are run.

Newcastle United were failed by an owner who didn’t see the magic or the history lying beneath the club. Those of us who grew up in the 2000s remember when they regularly turned over the biggest teams and were participating in Europe’s elite competitions. Their demise into mainstream mediocrity is what facilitated this takeover. Mike Ashley ignored years of pleas for investment from supporters who weren’t demanding success but dignity. While money will help solve current woes, these are solutions that could have been provided by fan ownership.

The feeling from many Newcastle fans is undoubtedly jubilant, and they will be right to have high expectations. Still, football is not merely about results. It’s about the moments and memories, and the feelings generated by them. It is true that the Premier League is at a higher standard than it was twenty years ago, but as more and more fans are priced out of attending matches, with stadiums being increasingly geared towards corporate customers – the glory of winning titles can be met with the emptiness of being frozen out of the club you love.

The game is dictated by money and that changes the mentalities of supporters too. We care more and more about how much money is spent or the biggest transfers. The spirit of competitive fairness is eroded too. Where there is such an enormous financial disparity, you cannot expect smaller clubs to challenge the bigger ones. This is a closed shop in everything but name. There is no risk for failure because clubs have the financial means to return next season. The size of their pockets guarantees redemptions and second chances. It would be a miracle for smaller clubs to try to compete with this for one year, let alone a sustained effort to match the brutal resources of wealthy clubs.

There will be relief and joy from some Newcastle fans, of course; nobody expects fans to be unhappy about their club’s good fortune. It might even be the case that this is good for the quality of the matches in the Premier League, capable of going toe to toe with Manchester City. But for all dreams of global domination and trophies, it will be impossible to avoid the feeling that the cost of these victories will be paid, at home and abroad, by crushing life out of the game.