The dividing line between the candidates to replace Boris Johnson is clear. Rishi Sunak is the “sound finance” candidate, while Liz Truss is the continuity Johnsonomics candidate.

Johnsonomics is not without its own critique – ultimately undermined by a decade of underprovision, making massive investments crumble through the grinding bureaucracy of “targeted support” schemes, while politically expedient regionalised spending fails to grasp the requirements of actual industrial policy in a climate crisis. Truss expresses these sentiments of spending via a lower tax take via corporation tax cuts, national insurance tax cuts, and new spending commitments for defence and health, which has so far been successful in convincing Parliamentary Conservative Party members.

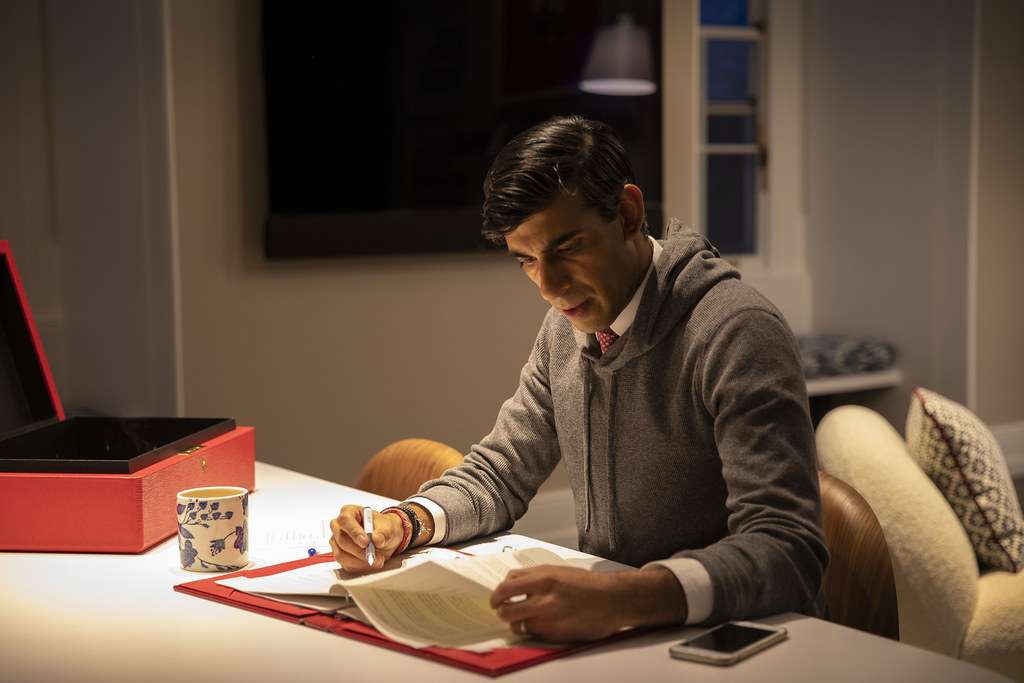

All candidates left in the wake of this contest pushed the potential balance sheet out – except one. The familiar arch-austerian Rishi Sunak has committed to reject “fairytale” economics, arguing that expansionary fiscal policy risks are “leaving a debt for our children to pay”. Combined with the embargo on new spending or taxation in the interim between leaders, Rishi Sunak hopes to inherit a cold, austere Government, determined to balance current spending at an accelerated rate. The trouble is this brand of “sensible” politics is about ten years out of date.

As we learned during the Coronavirus pandemic, the capacity for Government provision is not limited by its ability to build revenue. Working in the shadows with the Bank of England, almost all new spending over the pandemic was financed in the usual way – through new money creation, facilitated by a Bank of England’s mandate to support the government to drive down unemployment and encourage growth.

Adorned with the ability to finance its projects mostly as freely as it likes, the Government need not see ‘sense’ in a balanced budget. In fact, while the private sector continues to see higher deficits and reduced surpluses due to price pressures in the supply chain, depleting Government balances has the effect of worsening, if not causing further private losses – leading to unemployment, stunted growth, and recession.

Tory candidates who pledged corporation tax cuts are not free of fairytale thinking though – just a different fairytale. The idea that by simply cutting taxes, businesses will make further investments in themselves, their workers, and their local economies, is long debunked. It once knew its name as the ‘Laffer curve’, and has long been a mainstay of right wing economic myth. Utilising the state’s great capacity to do without revenue in this way is a fantasy that makes the Treasury busy with nuisance policy, instead of dealing with the issue at hand: getting people’s wages to go further, and getting higher wages out of firms and public institutions.

This line of thought has been the prevailing narrative since the late 80s, yet the model was made myth with the emergence of COVID-19, as decades of underinvestment in everything from nationalised healthcare, to private communications infrastructure, to wages, all revealed themselves in the wake of a serious economic interruption. Tory Britain’s fantasy of a lean, adaptive state was revealed instead to be starved, desperate, and unable to cope.

Disgracefully, NHS waiting lists are the longest they’ve been since 2007, with over 6,700,000 patients awaiting medical help. Critical fuel storage in the UK has depleted by over 70% due to the closure of Centrica’s Rough facility in 2017. The COVID-19 Universal Credit uplift remains a sorry reminder of this government’s inability to consider welfare as an economic directive, with retail confidence in the UK now at a record low.

A sensible fiscal policy recognises these strategic flaws and doesn’t focus on the cooked books of the Treasury balancing revenue with outlay – instead, it focuses its vision on deploying real resources, achieving full employment, and investigating the inflationary aspects of new policy, not simply trading in cumbersome higher or lower meta-economics.

If Labour want to properly oppose the new government, whoever they are led by, they must resist the temptation to deploy questions of affordability. There are more intricate and valuable critiques to be made that cannot simply be thrown back at Rachel Reeves – and could even go as far as redefining the term ‘economic competence’ in general. Labour has a world to win, with Red Wall voters preferring an economic strategy that prioritises provision above the urge to balance the books. It is up to Labour whether or not they want to be a temporary diversion in the Conservative story of economics in politics, or whether they want to finally close the chapter on this 40 year long book for good.