On Thursday the Financial Times reported that the Labour party had watered down plans to strengthen workers’ rights in an attempt to woo corporate leaders and discredit Tory party claims that Labour is “anti-business”. The two main areas the FT reported Labour’s watering-down had occurred were on its pledge to create a single status of ‘worker’ for all but the genuinely self-employed, and on its pledge to introduce day-one employment rights for employees (rather than the two years workers currently have to wait to gain access to them). The trouble with this reporting is that neither of these two word changes in the policies represent meaningful backsliding on Labour’s ambitious raft of employment reforms from its New Deal For Working People green paper. The FT’s article has prompted Deputy Labour leader Angela Rayner to clarify that “Far from watering it down, we will now set out in detail how we will implement it”.

This is not to say that there isn’t a culture of backsliding developing across all areas of Labour policy at the moment. From when Labour announced it would not commit to abolishing tuition fees, it has been open season on any and all “unfunded” spending commitments in the name of the Labour leader’s embrace of “fiscal conservatism”. As well as reneging on their commitment to abolish the two child benefit cap, Labour’s pledge to spend £28 billion per year on a green transition has also been watered down to a commitment to gradually reach the £28 billion figure once Labour entered government. The list of U-turns made by the Labour party since Keir Starmer took office remains ever-growing.

Given this context, it’s easy to see why Unite have accused Labour of attempting to “curry favour with big business” by changing the wording of the two policies. However, the fundamental issue with the specific changes reported by the FT is their vagueness. Interpretation is entirely in the eye of the beholder on the single status of worker, the FT reported:

Instead of introducing the policy immediately, Labour has agreed it would consult on the proposal in government, considering how “a simpler framework” that differentiates between workers and the genuinely self-employed “could properly capture the breadth of employment relationships in the UK” and ensure workers can still “benefit from flexible working where they choose to do so”.

What shape the consultation takes will define how the policy is implemented – but this is true of any new employment policy, all of which will go through periods of consultation on their journey to becoming law. The current employment framework means that the self-employed, “limb b workers”, and agency workers all have fewer rights than employees (with agency workers gaining employee rights after twelve weeks working for the same employer). At present, self-employed people have almost no protection under employment law; limb b workers have some rights, like holiday pay and the minimum wage, but no entitlement to rights like Statutory Sick Pay, Statutory Maternity and Paternity Leave, time off for emergencies, and more. Establishing a single status of “worker” would mean all workers were entitled to the same rights as employees.

When the consultation does arrive, the true debate will be had when it comes to how the word “flexibility” is defined. For Uber, their definition is what has ultimately resulted in governments around the globe siding with them against their own drivers. Uber is just one company with a publicly acknowledged interest in single worker status not becoming law (and has a war chest of £75 million per year set aside to lobby governments on the matter).

But Uber provides a good case study of the radicalism of Labour’s New Deal For Working People. Uber has continued to selectively implement the Supreme Court ruling which first classified their drivers as “workers” in 2021. One of the original Supreme Court case’s claimants, ADCU General Secretary and former Uber driver James Farrar, recently had to take Uber to the Employment Tribunal to win the £20,000 owed to him in unpaid holiday pay and minimum wage commitments. Even Labour’s most basic pledge on workers’ rights, of establishing a Single Enforcement Body to enforce employment law, would make it harder for companies like Uber to dodge their existing legal obligations. Extending the time period in which claims can be brought to the Employment Tribunal (another policy from the New Deal For Working People) would mean law breaking companies could be held to account more effectively by their workers and former workers.

In essence, even the most basic of reforms listed in the New Deal For Working People would make law-breaking employers’ lives harder and their workers’ lives better.

On the day-one employment rights for all employees pledge, the FT reported that:

Labour also clarified that its previously announced plans to introduce “basic individual rights from day one for all workers”, including sick pay, parental leave and protection against unfair dismissal, will “not prevent . . . probationary periods with fair and transparent rules and processes.”

Again, it’s difficult to frame this as an abandonment or watering-down of a pledge when so little detail is given on how long the probationary period mentioned will be. Given this vagueness, it is not surprising that trade union officials are said to remain “very happy” with the policy as it currently exists even with the clarifications reported in the FT.

If the Labour leadership wanted to water down the New Deal For Working People, a difficulty would be finding a place to start. It is a uniquely policy-rich document, which includes:

- Fair pay agreements

- Single status of “worker”

- Give all workers rights from day one

- Ban zero hours contracts

- Increase Statutory Sick Pay and expand access to it

- Outlaw fire and rehire

- Make flexible working a day-one right

- Bring in the right to switch off and work autonomously

- Extending Statutory maternity and paternity leave

- Repeal the Trade Union Act 2016 and make union recognition easier

- Establish a Single Enforcement Body (SEB)

- Extending the time period for bringing claims to the Employment Tribunal

- And more

The direction of travel of Starmer’s leadership is clear: close off Tory attack lines by reneging on previous spending commitments. It’s difficult to read the news at the moment without coming across news of another Labour U-turn, and it is not unfair to ask the question “If Labour won’t abolish the two child benefit cap, what will they do?” But on workers’ rights the benefit of reneging on previous commitments doesn’t actually close off Tory attack lines now as much as it would restrict a future Labour government’s ability to do anything in office. If Labour did renege on huge parts of its New Deal For Working People green paper, it would create a rift with unions, who give huge amounts of money to the Labour party.

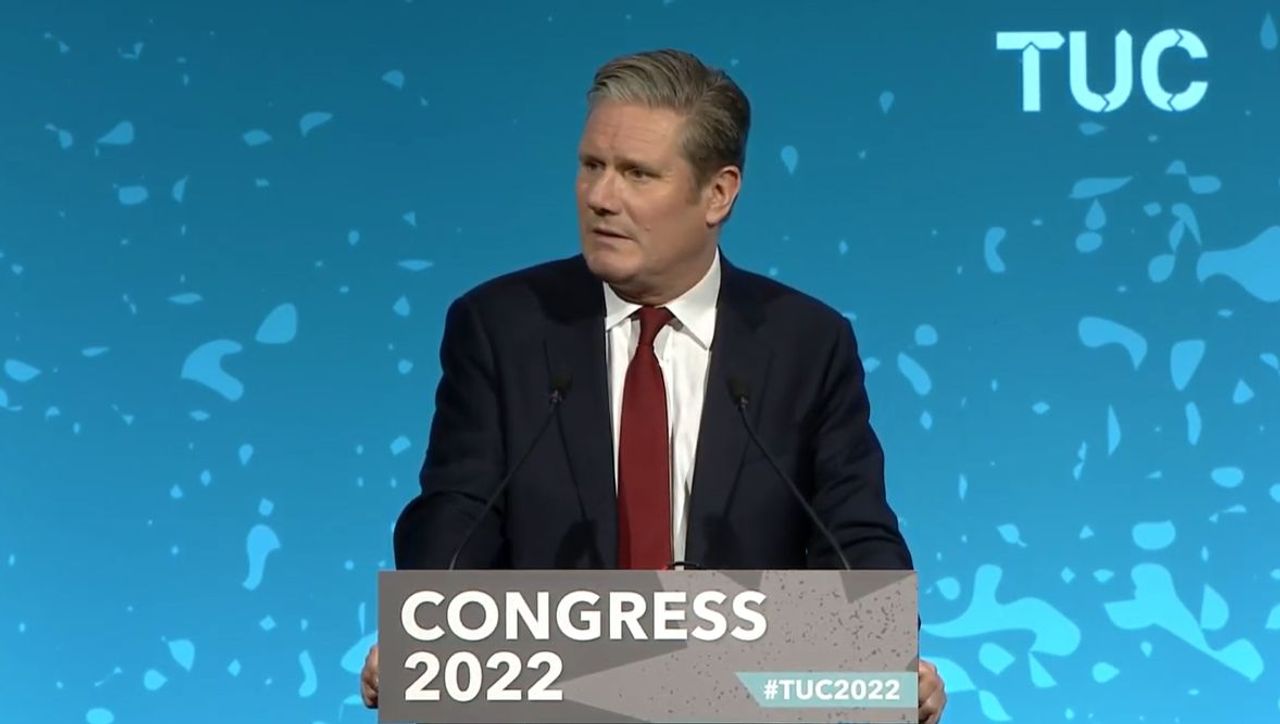

Starmer’s 2022 speech to the TUC, given during Liz Truss’ brief tenure as Prime Minister, remains as true today as when it was given on the subject of Labour’s New Deal For Working People:

Nobody does their best work if they’re wracked with fear about the future. If their contract gives them no protection to stand up for their rights at work. Or if a proper safety net doesn’t support them in times of sickness and poor health. That’s what Labour’s New Deal for Working People is about. That’s why we’ll end fire and rehire, ban zero-hour contracts, extend parental leave, strengthen flexible working, better protections for pregnant women, mandatory reporting on ethnicity pay gaps, statutory sick pay for all, a single worker status, no more one-sided flexibility! As far as I’m concerned, that’s not just a list of rights. It’s a statement of intent on social justice. On fairness. Whose side we are on. More security for every worker in our country. And because of that – a stronger foundation for working people to aspire and get on. That’s the economic dynamism Britain needs. That’s how you get growth. That’s the Labour choice.

Labour is currently in a holding pattern of pronouncing what they won’t do and can’t fight for. But reneging on their workers’ rights commitments wouldn’t be a sign they were pro-business; it would be a sign they had become pro-exploitation. Any change in any aspect of the New Deal For Working People deserves significant scrutiny, ultimately what will matter isn’t the National Policy Forum document, or what the policy looks like in October – but what is written in the manifesto and implemented by a Labour government. Considering the amount of enemies Labour would make of supportive stakeholders, and bearing in mind how difficult the pledges would be to unpick, there are few tangible benefits that Labour would see from reneging on their workers’ rights commitments. At present it does not appear any such reneging has taken place.